- Last updated on .

- Hits: 4488

The Cathars in Languedoc

Catharism was a Christian religious sect that appeared in the Languedoc in the 11th century and flourished in the 12th and 13th centuries. It is argued that Catharism spread to Europe from Armenia and Bulgaria, although this is hotly debated by historians. Originally, the Cathars did not have a name for themselves - simply referring to themselves as only as Bons Hommes et Bonnes Femmes (Good Men and Good Women). One popular theory on the origin of the name Cathar is that it derived from ancient Greek: Katharoi, meaning "pure ones". Confusingly, the Cathars were also sometimes referred to as the Albigensians. This name originates from the end of the 12th century, and was used by the chronicler Geoffroy du Breuil of Vigeois in 1181. The name refers to the ancient Languedoc town of Albi. The use of the name came from the fact that a debate was held in Albi between priests and the Cathars. However, few inhabitants of Albi were ever actually Cathars, and the city gladly accepted Catholicism during the crusade.

Catharism was a Christian religious sect that appeared in the Languedoc in the 11th century and flourished in the 12th and 13th centuries. It is argued that Catharism spread to Europe from Armenia and Bulgaria, although this is hotly debated by historians. Originally, the Cathars did not have a name for themselves - simply referring to themselves as only as Bons Hommes et Bonnes Femmes (Good Men and Good Women). One popular theory on the origin of the name Cathar is that it derived from ancient Greek: Katharoi, meaning "pure ones". Confusingly, the Cathars were also sometimes referred to as the Albigensians. This name originates from the end of the 12th century, and was used by the chronicler Geoffroy du Breuil of Vigeois in 1181. The name refers to the ancient Languedoc town of Albi. The use of the name came from the fact that a debate was held in Albi between priests and the Cathars. However, few inhabitants of Albi were ever actually Cathars, and the city gladly accepted Catholicism during the crusade.

Cathars in Languedoc - what was Catharism?

The Cathars claimed an Apostolic succession from the founders of Christianity and saw Rome as having betrayed and corrupted the original purity of the message. Cathars believed in two principles, a good creator god and his evil adversary (much like God and Satan of mainstream Christianity). Cathars called themselves Christians, but the current theology of the Catholic church describes them as non-Christians. Catharism was above all a populist religion and the numbers of those who considered themselves "believers" in the late twelfth century included a sizable portion of the population of Languedoc, counting among them many noble families and courts.

Cathars maintained a religious hierarchy (between ordinary believers and the Perfecti, who led very frugal lives). Many Cathars were weavers of cloth - indeed during the subsequent Inquisition, weavers were (often wrongly) accused of spreading the Cathar theology in their designs (just like the Huguenot Protestants, were similarly accused in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries). The Cathars eschewed the idea of priesthood or the use of church buildings, but they did have some elaborate ceremonies. Cathars believed in reincarnation and refused to eat meat or other animal products. They were strict about biblical rules - notably those about living in poverty, not telling lies, not killing and not swearing oaths. Many of their beliefs – equality for men and women, no objection to contraception or suicide, denial that Jesus could become incarnate and still be the son of God, rejection of Capital punishment, disapproval of church corruption and opulence – were at odds with the Catholic Church, which led to them being branded as heretics and ruthlessly pursued in a series of crusades.

Cathars in Languedoc

During this period an estimated 500,000 Languedoc men women and children were massacred - Catholics as well as Cathars. Educated and tolerant Languedoc rulers were replaced by less enlightened rulers. Learning was discouraged and the reading of the bible became a capital crime. Tithes were enforced. The Languedoc started its long economic decline to become the poorest region in France. The language of the area, Occitan, began its descent from the foremost literary language in Europe to a regional dialect, disparaged by the French as a patois. The crusade against the Cathars of the Languedoc has been described as one of the greatest disasters ever to befall Europe.

During this period an estimated 500,000 Languedoc men women and children were massacred - Catholics as well as Cathars. Educated and tolerant Languedoc rulers were replaced by less enlightened rulers. Learning was discouraged and the reading of the bible became a capital crime. Tithes were enforced. The Languedoc started its long economic decline to become the poorest region in France. The language of the area, Occitan, began its descent from the foremost literary language in Europe to a regional dialect, disparaged by the French as a patois. The crusade against the Cathars of the Languedoc has been described as one of the greatest disasters ever to befall Europe.

The Cathar Crusade in Languedoc

The Catholic Church regarded the Cathar sect as dangerously heretical. Faced with the rapid spread of the movement across the Languedoc region the Church first sought peaceful attempts at conversion, undertaken by Dominicans. These were not very successful, and things took a turn for the worse for the Cathars, after the murder on 15 January 1208 of the papal legate Pierre de Castelnau by a knight in the employ of Count Raymond of Toulouse. This was unfortunate on two counts for the Cathars. Firstly, on a point of technicality, the assassination had little to do with the Cathars themselves and had more to do with the fact that the The Papal Legate had involved himself in a dispute between the rivals Count of Baux and Count Raymond of Toulouse. Secondly, the assassination was used by the Church as a justification for a religious crusade against the Cathars. The crusade, which the French enthusiastically carried out, was known as the Albigensian Crusade. The Crusade, and the inquisition which followed it, entirely eradicated the Cathars from the Languedoc. The Albigensian Crusade was undertaken by the French for mainly political purposes as it enabled France to conquer the until then independent principalities, such as Toulouse, of Southern France. The excuse of eradicating the Cathars in Languedoc led to a massive genocide in the South of France - a largely hollow victory given the huge numbers of warriors under the command of Simon de Montfort and the largely pacifistic nature of the Cathars themselves (killing was abhorrent to Cathars).

Simon de Montfort - the unwelcome Languedoc tourist

The French King (Phillip) refused to lead the crusade himself, nor could he spare his son Louis. Phillip did however sanction the participation of some of his more bellicose and ambitious barons, notably Simon de Montfort and Bouchard de Marly. There followed 20 years of war against the Cathars and their allies in the Languedoc. This war pitted the nobles of the north of France against those of the south. The widespread northern enthusiasm for the Crusade was partially inspired by a papal decree permitting the confiscation of lands owned by Cathars and their supporters. As the Languedoc was supposedly teeming with Cathars and Cathar sympathisers, this made the region a target for French noblemen looking to acquire new fiefs.

The French King (Phillip) refused to lead the crusade himself, nor could he spare his son Louis. Phillip did however sanction the participation of some of his more bellicose and ambitious barons, notably Simon de Montfort and Bouchard de Marly. There followed 20 years of war against the Cathars and their allies in the Languedoc. This war pitted the nobles of the north of France against those of the south. The widespread northern enthusiasm for the Crusade was partially inspired by a papal decree permitting the confiscation of lands owned by Cathars and their supporters. As the Languedoc was supposedly teeming with Cathars and Cathar sympathisers, this made the region a target for French noblemen looking to acquire new fiefs.

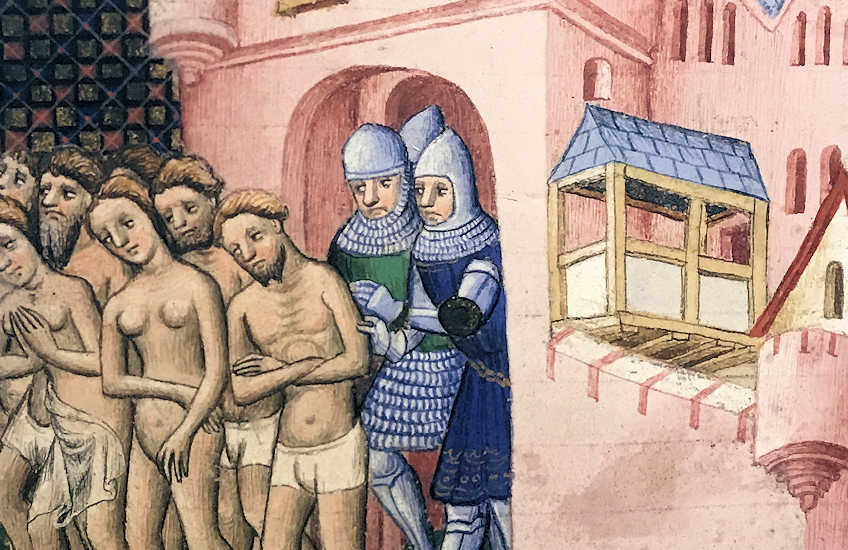

In the first significant engagement of the war, the town of Béziers was besieged on 22 July 1209. The Catholic inhabitants of the city were granted the freedom to leave unharmed, but many refused and opted to stay and fight alongside the Cathars. Arnaud, the Cistercian abbot-commander of the Crusader Army, is supposed to have been asked how to tell Cathars from Catholics. His reply, was short and too the point "Kill them all, the Lord will recognise His own." The doors of the church of St Mary Magdalene were broken down and the refugees dragged out and slaughtered. Reportedly, 7,000 people died there including many women and children. Elsewhere in the town many more thousands were mutilated and killed. Prisoners were blinded, dragged behind horses, and used for target practice.[9] What remained of the city was razed by fire. Arnaud wrote to Pope Innocent III, "Today your Holiness, twenty thousand heretics were put to the sword, regardless of rank, age, or sex.". The permanent population of Béziers at that time was then probably no more than 5,000, but local refugees seeking shelter within the city walls could conceivably have increased the number to 20,000.

Following the massacre at Beziers, Simon de Montfort laid siege to the Trencavel capital of Carcassonne, eventually taking it by (some would argue) duplicitous methods - imprisoning Raymond Roger, the Trencavel Lord, in his own citadel where he later died (apparently by natural causes - although you will not find many people in Languedoc who belive this official version of events).

The war ended in the Treaty of Paris (1229), by which the king of France took most of the lands of the house of Toulouse and all of the lands of the Trencavels (Viscounts of Béziers and Carcassonne). The independence of the princes of the Languedoc was at an end. But in spite of the wholesale massacre of Cathars during the war, Catharism was not yet extinguished.

The Inquisition of the Cathars

The Inquisition was established in 1229 by the Catholic church to uproot the remaining Cathars in Languedoc. Operating in the south at Toulouse, Albi, Carcassonne and other towns during the whole of the 13th century, and a great part of the 14th, it finally succeeded in extirpating the movement.

From May 1243 to March 1244, the Cathar fortress of Montségur was besieged. On March 16, 1244, a large and symbolically important massacre took place, where over 200 Cathar perfects were burned in an enormous fire at the foot of the castle. A popular theory holds that a small party of Cathar Prefecti escaped from the fortress before the massacre and took with them Cathar treasure. What this treasure consisted of has been a matter of considerable speculation: claims range from sacred Gnostic texts to the Cathars' accumulated wealth. This interest in the Cathar treasure even reached the ears of the Nazis and in particular, Heinrich Himmler, who despatched an archaeologist in search of the possible Holy Grail.

Hunted by the Inquisition and without the backing of their powerful nobles, the Cathars became scattered fugitives throughout the Languedoc region: meeting surreptitiously in forests and mountains. Later insurrections broke out under the leadership of Bernard of Foix, Aimery of Narbonne and Bernard Délicieux. But by this time the Inquisition had grown very powerful. Many suspected Cathars were summoned to appear before it. The Prefecti only rarely recanted, and hundreds were burned at the stake. Repentant lay believers were punished, but their lives were spared as long as they did not relapse. Having recanted, they were obliged to sew yellow crosses onto their outdoor clothing and to live apart from other Catholics, at least for a while.

Catharism is often said to have been completely eradicated by the end of the fourteenth century.

Cathar country in Languedoc?

After the suppression of Catharism, the descendants of Cathars were at times required to live outside towns and their defences. They thus retained a certain Cathar identity, despite having returned to the Catholic religion. The Cathars have in recent times been depicted in popular books such as The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail as a group of elite nobility somehow connected to "secrets" about the true nature of the Christian faith. Today, Cathar Country ("Pays Cathare") is promoted by regional authorities to highlight the Cathar heritage and history of the Languedoc region. Some have argued however that there are major historical errors at work here. For example, the castle of Montségur was razed after 1244; the current fortress follows French military architecture of the 17th century. Other examples include the magnificent castles of Queribus and Peyrepetuse which are both perched on the side of dramatic escarpments in the Corbieres mountains. These castles were for several hundred years frontier fortresses belonging to the French crown and most of what you will see there today dates from a post-Cathar era. Indeed, there is little evdience to suggest that Cathars laid one stone in any fortification. Clearly, Montsegur was a Cathar refuge and a group of Cathars, briefly took refuge in Queribus - but the link between the citadels and Catharims is otherwise virtually non-existent.

After the suppression of Catharism, the descendants of Cathars were at times required to live outside towns and their defences. They thus retained a certain Cathar identity, despite having returned to the Catholic religion. The Cathars have in recent times been depicted in popular books such as The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail as a group of elite nobility somehow connected to "secrets" about the true nature of the Christian faith. Today, Cathar Country ("Pays Cathare") is promoted by regional authorities to highlight the Cathar heritage and history of the Languedoc region. Some have argued however that there are major historical errors at work here. For example, the castle of Montségur was razed after 1244; the current fortress follows French military architecture of the 17th century. Other examples include the magnificent castles of Queribus and Peyrepetuse which are both perched on the side of dramatic escarpments in the Corbieres mountains. These castles were for several hundred years frontier fortresses belonging to the French crown and most of what you will see there today dates from a post-Cathar era. Indeed, there is little evdience to suggest that Cathars laid one stone in any fortification. Clearly, Montsegur was a Cathar refuge and a group of Cathars, briefly took refuge in Queribus - but the link between the citadels and Catharims is otherwise virtually non-existent.

Still, that would spoil the story somewhat. My view is that these remnants are symbolic of Catharism and the ruthless methods deployed to extinguish this enlightened religion. When you see how remote these Castles are, you will also see how desperate the Cathars must have been to search for peace and security to practice their way of life. The Cathars in Languedoc is an improtant story worth telling because it helps explain how this beautiful region of Southern France has been regarded throughout history as France's ugly sister.

For more information about the Cathar's in Languedoc please visit http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cathars or http://www.cathar.info/